WHAT WOMEN CAN EXPECT FROM STRENGTH TRAINING, EXPLAINED BY SCIENCE

— The 7 Minute Read —

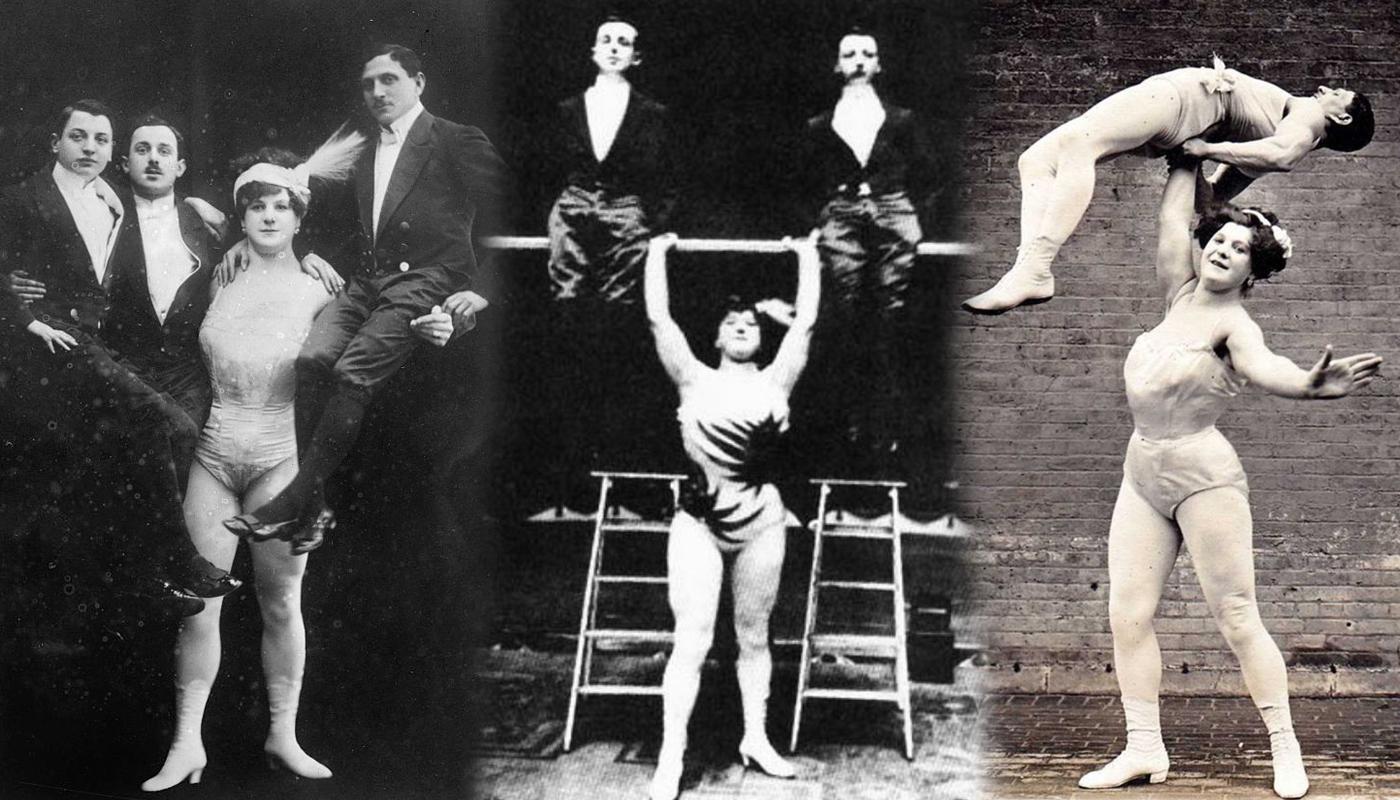

Katharina Brumbach, born in Vienna, Austria in 1884, emerged as a figure who remains celebrated as one of history's most formidable female athletes. Standing tall at 6′ 1″ (185 cm), she adopted the name “Katie Sandwina” in the early 1900s following her victory over Eugen Sandow in a weightlifting competition. Sandow is regarded as "The Father of Bodybuilding". He acquired that title for good reason, having pioneered groundbreaking strength training techniques still utilised today. Considered the epitome of male physical perfection in his time, Sandow was famed for his extraordinary feats of strength.

Returning to Katharina Brumbach's remarkable accomplishment, she and Sandow engaged in a riveting lifting challenge, culminating in both facing a 300 lb (136kg) dumbbell. Brumbach astounded by hoisting it overhead with one arm, whereas Sandow could only lift it up to his chest. Thus, Brumbach earned the name Sandwina, a tribute to the illustrious Sandow.

Since Katie Sandwina's exploit more than a century ago, the narrative surrounding women's involvement in strength training underwent a gradual transformation. Breaking through the barriers within this traditionally male-dominated domain and challenging prevailing social norms was no small feat.

As perceptions shifted, researchers began considering that training methodologies for both men and women should perhaps be more individualised, or at the very least, acknowledge that women's training requirements may differ due to factors such as menstrual cycles, menopause, pregnancy, body composition, hormonal profiles, hydration needs, etc. However, determining which variances are significant and whether adjustments to training guidance are warranted remains an ongoing debate.

In response to this evolving landscape, researchers from three continents embarked on a comprehensive systematic review, published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. Their primary objective was to delve into the nuances of how women respond to resistance training and identify the critical variables that contribute to strength and muscle gains in female participants. The review encompassed a wide range of studies, considering factors such as training frequency, intensity, volume, and duration.

The researchers reviewed 40 studies encompassing 1,312 women aged 18 to 35. These studies featured mostly untrained or inactive participants, with some including individuals described as "physically active." Only one study involved participants with prior strength training experience.

The main outcome was that strength training worked — duh! Assessments of both strength and muscle size, conducted through various methods such as MRI, CT scans, and ultrasound, revealed statistically significant improvements. Muscle mass experienced a notable increase, showing improvement for most participants, while strength exhibited a more modest enhancement, suggesting that not all subjects experienced significant progress.

Practically speaking, studies indicating a higher frequency of workouts per week produced greater increases in muscle mass, while those with a greater total number of weekly sets demonstrated larger gains in strength. Despite the median of 72 sets per week in the meta-analysis, it's somewhat surprising that the highest volumes yielded the most significant results—considering that 72 sets is already a substantial workload. This equates to completing three sets of eight different exercises, three times a week, which exceeds the minimum thresholds for effective strength training. The authors suggest that previous research hints at women possessing higher fatigue tolerance and faster recovery capacity compared to men. Consequently, women may derive greater benefits from higher volumes of training compared to men.

Despite this progress, ambiguity persists regarding which differences between men and women in training responses are truly significant. While some disparities may be negligible or even nonexistent, others may warrant significant adjustments to training guidance. Consequently, there is a growing call for more comprehensive research that directly compares the training responses of men and women under identical conditions. Such studies are crucial for determining whether gender-specific training approaches are essential for optimising performance and achieving desired outcomes.